The Village Health Assistants Transforming Maternal Care in PNG

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is one of Australia’s closest neighbours, but for many women, the realities of pregnancy and childbirth are often dramatically different from what most Australians…

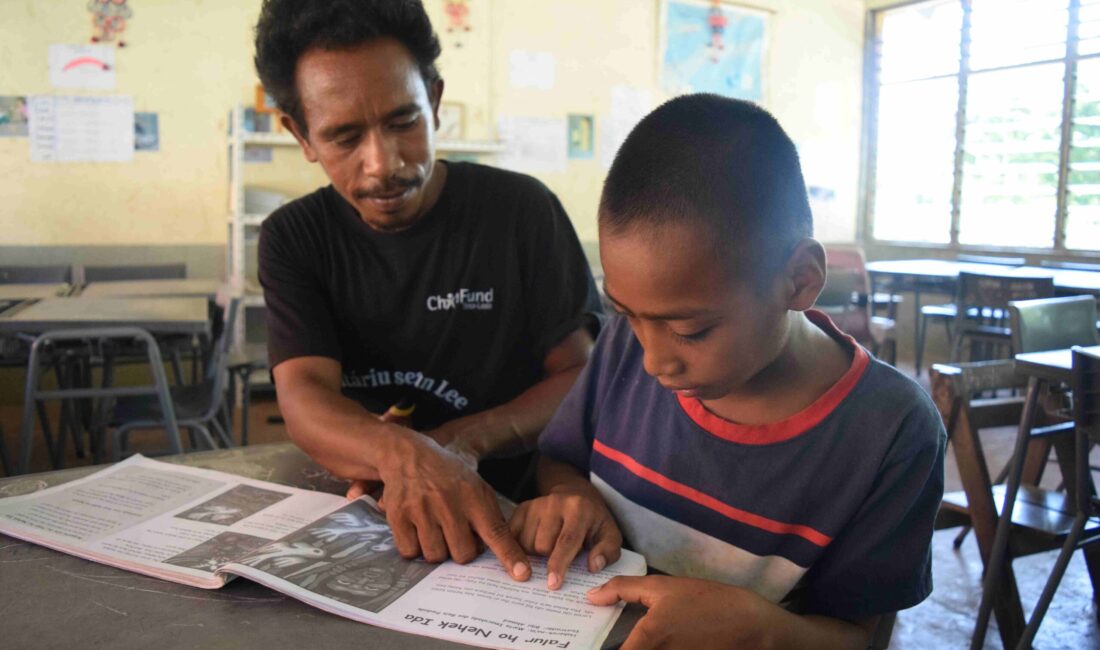

Understanding child marriage: causes, impact and solutions

Child marriage affects millions of children around the world, denying them the opportunity to grow, learn and reach their full potential. While global rates have declined in recent decades, child…

Growing up healthy: Why childhood vaccinations are important

Learn more about how ChildFund is improving childhood vaccination rates in Papua New Guinea.

How we help malnourished children

Lily weighed a healthy 3kg when she was born, however eight months later she stopped eating.