When disasters strike, Australians have time and time again demonstrated a strong willingness to contribute to humanitarian aid efforts around the globe. Yet, the scale of the challenge is more immense than ever, with an estimated 305 million people [1] requiring urgent humanitarian assistance.

We spoke to ChildFund Australia’s Director of Programs, Sophie Jenkins, to explore key questions:

- What is humanitarian aid?

- How is it coordinated?

- Who provides humanitarian aid?

- What challenges lie ahead?

What is humanitarian aid?

The definition of humanitarian aid refers to the immediate assistance provided in the aftermath of disasters like cyclones or earthquakes, or armed conflict. The goal of humanitarian aid is to:

- Save lives,

- alleviate suffering, and

- maintain human dignity.

Humanitarian aid is vital for addressing the immediate needs of affected communities and laying the foundation for long-term recovery.

Type of Humanitarian Aid

The types of humanitarian aid vary depending on the nature of the crisis. Common categories include:

- Food assistance to address hunger and malnutrition.

- Shelter support, including temporary housing and materials.

- Health services, such as mobile clinics or emergency care.

- Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), ensuring access to clean water and safe waste disposal.

- Non-food items (NFIs) such as blankets, cooking utensils, and hygiene kits.

- Psychosocial support, helping individuals deal with trauma and grief.

These are just a few humanitarian aid examples that play a critical role in disaster response.

Current humanitarian emergencies that ChildFund Australia supports

Across the world, humanitarian emergencies are becoming more protracted and harder to address. ChildFund Australia and ChildFund Alliance members work with partners in some of the most protracted crises across the world including Afghanistan, Myanmar and Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh.

ChildFund’s Response in Myanmar

In late March 2025, two devastating earthquakes shattered entire communities, forcing children and their families into makeshift shelters and pushing essential services like running water, sanitation and healthcare to the brink of collapse.

This was Myanmar’s deadliest quake in decades, claiming over 3000 lives and injuring 5,000. More than 28 million people were affected across six regions. Our ChildFund Myanmar team and local partners quickly mobilised to support affected families.

Their first priority was to equip local emergency response teams with the tools they needed to save lives. We delivered essential items, including helmets with headlamps, clean water, surgical masks and gloves to 12 local rescue groups. One team leader expressed what difference this support made in their efforts to dig people out of the rubble in time, “We have utilized the items provided not only for our team but also for another local rescue team that was in urgent need. We sincerely appreciate the generous support from donors for our affected communities.”

Who provides humanitarian aid?

Humanitarian aid is not a single-handed effort, but a coordinated response involving a range of partners. This includes:

- National governments, which are central to leading and coordinating responses.

- United Nations agencies, such as UN OCHA, UNICEF and the World Food Programme.

- International humanitarian aid organisations like ChildFund Australia.

- Local non-government organisations (NGOs) working in affected communities.

- Private sector partners, including logistics and communications companies.

The most effective humanitarian responses are led by local communities and organisations, guided by their local knowledge and needs. Why? Because it is the humanitarians living and working in affected communities who are the first to respond during a crisis. They possess deep local knowledge and established networks that are crucial for effective, sustainable humanitarian action. This on the ground expertise ensures that aid is guided by what people need, rather than by an external plan.

Does Australia ever receive emergency assistance?

Yes. While Australia is a donor to many global emergencies, we also receive support during domestic disasters when needed. For example, during the 2019–20 Black Summer bushfires, the Australian government received international emergency assistance from the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom to help fight fires and support recovery efforts.

This underscores that even wealthy nations benefit from emergency assistance in times of extreme crisis.

Measuring the impact of humanitarian aid

The humanitarian aid sector uses well-established indicators to measure success. For instance, a universal benchmark in water, sanitation, and hygiene programs is ensuring every person in an affected population has access to at least 15 litres of water per day for drinking and hygiene.

Such metrics are critical in assessing the effectiveness and accountability of humanitarian aid programs.

Key humanitarian aid issues of the 21st century

Today’s humanitarian landscape is shaped by increasingly frequent and complex crises. Major emergencies include:

A lack of funding, access constraints or direct attacks on aid workers regularly impact the ability of humanitarians to respond, and the consequences of which can be devastating for communities at risk.

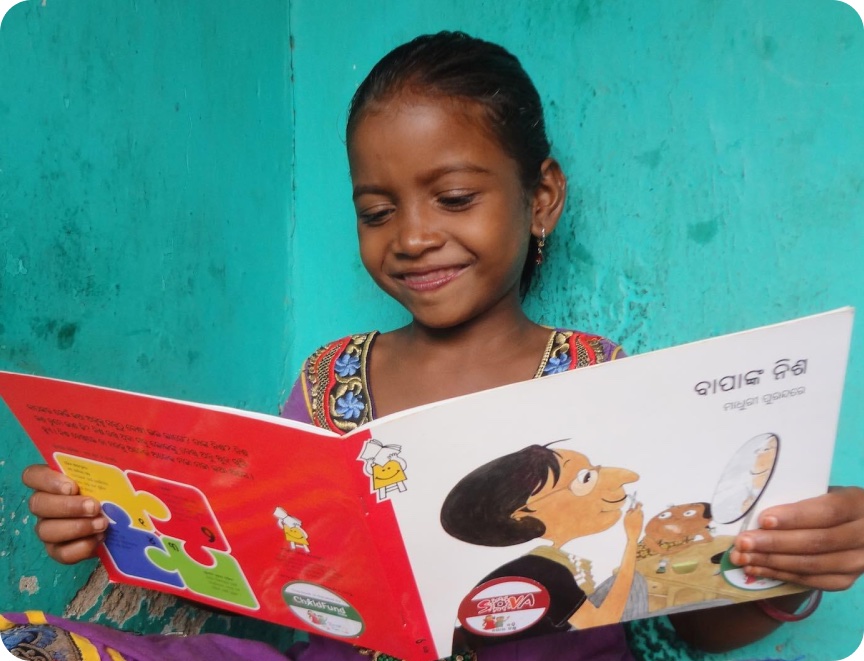

Support ChildFund Australia’s humanitarian aid efforts

In times of crisis, children are among the most vulnerable. Whether facing conflict, disasters or food insecurity, they need immediate and sustained support to survive and recover.

ChildFund Australia’s response provides life-saving humanitarian aid including:

- clean water,

- food,

- shelter, and

- psychosocial care.

You can make a difference where it’s needed most. By becoming a monthly donor, you’ll help us respond swiftly when emergencies strike — providing children and families with the care and support they need. Become a monthly donor today.

(1) Global Humanitarian Overview 2025, OCHA

In August, the first-ever Pacific Cyber Week was held in Fiji, bringing together governments, civil society and industry to progress action on cyber threats. For small island states, everyday online harms aren’t abstract or theoretical. They are happening right now, through scams targeting remittance payments, data-hungry apps in schools and AI systems arriving faster than regulation.

With Australia supporting the arrival of high-speed internet in the Pacific, it’s imperative that that we support communities to harness the benefit, and Australia, and its partners, keep clear sight of the duty to ‘do no harm’. That means we can’t separate cybersecurity from the very people who are impacted by cyber harms.

Every half second, a child goes online for the very first time. That’s a staggering 63 million new users each year. It’s no longer a matter of if but when a child will face online harm. In this blog, ChildFund Australia’s Senior Policy Advisor, Jacqui McKenzie, breaks down how we make the internet work better for children, offering practical takeaways for anyone concerned about child safety online.

Children’s privacy: The 72 million data point problem

Have you ever stopped to think about what happens when a child’s entire digital life is tracked?

By age 13, an estimated 72 million data points have been collected on a single child. Experts are calling this the “datafication of childhood.” Their data is widely collected, with too few controls, and not enough accountability.

This isn’t just about their favourite shows. It’s a deep, personal profile built from their likes, search history, watch time and spending habits. This data shapes their online world, allowing platforms to target them with everything from personalised streaming recommendations to deceptive advertisements, and in some cases, much more harmful content.

The reality is that as kids spend more time online, their digital experiences are increasingly shaped by commercial platforms that record, track and analyse almost everything they do – often for profit. This digital footprint follows them for life and can lead to irreversible harm. It makes them vulnerable to identity theft, scams and the sale of their live location data. Even when handled by legitimate companies, children’s data can be used design addictive features or sold to third parties.

This raises a critical question: How can we protect children’s data? The reality is sobering. In many countries, children have no more data protection than adults.

A Children’s Privacy Code can set clear boundaries and lift standards to protect data. A code would go beyond voluntary guidelines and focus on enforceable standards. In Australia, a Children’s Privacy Code will be finalised in 2026 and this should include enforceable rules that:

- Ensure services that children use have the strongest privacy settings turned on, by default.

- Minimise data collection by design. This means services should not collect anything more than what they need to provide a service.

- Ban targeted advertising and profiling of children.

- Prohibit precise geolocation for minors except in strictly defined cases.

- Require risk assessments and mitigation strategies for services aimed at children or likely to be accessed by children.

- Safeguard ed-tech. This means no third-party trackers, clear data maps and prohibiting onward sale of children’s data.

- Mandate plain-language privacy notices children and parents can actually understand.

Regulation is a non-negotiable for holding platforms accountable for user safety and protecting children from online harm. However, this is only half the solution. Regulation should work in tandem with community-based initiatives that support everyone to navigate the digital world safely.

The importance of digital literacy

Discussions at the conference made one thing crystal clear: you cannot divorce cybersecurity from the people it’s meant to protect. While infrastructure, firewalls and incident response is vital, protection starts with prevention and a core part of that is digital literacy. This isn’t a luxury – it’s a necessity, especially for children.

Young people are growing up having to navigate online environments designed to capture their attention and data, where every click, search and share could expose them to risk. Therefore, a truly protective approach to online safety must include age-appropriate digital literacy education from early adolescence. This includes:

- Critical thinking skills: Learning to question what you see online and understanding that a seemingly harmless post, like or photo could be used in ways you never intended.

- Navigating privacy settings and scams: We must equip young people with the practical skills to manage their digital lives. This includes teaching them how to effectively use privacy settings to control how their personal data is used, as well as how to identify and avoid scams, malicious content and people.

- Building the confidence to seek help: Online harm can be isolating. Children should know that it’s okay to ask for help and be provided with clear paths to do so. This means building their confidence to reach out to a trusted adult – whether that be a parent, teacher or caregiver – if they encounter something that makes them feel unsafe or uncomfortable online.

Building skills to enhance safety is necessary and digital literacy must be scaled up quickly to meet the pace of the challenge.

How does this work in regions like the Pacific? Schools are an important intervention, but community-based approaches are crucial where the geographic spread is considerable.

This is where real-world solutions like Swipe Safe come in. Launched by ChildFund Australia in Vietnam in 2017, Swipe Safe fills a critical gap in digital literacy education for children in the Asia-Pacific region. This program takes a comprehensive approach to digital literacy, providing age-appropriate education and skills building resources for young people aged 10-18. It uses interactive learning and practical examples to support children to make the most of what the internet can offer them. To date, Swipe Safe has reached over 60,000 young people across 10 countries.

Human rights must be the backbone of national AI strategies

As we empower young people with digital literacy skills, we must also ensure that the technologies they use are built on a solid foundation of safety and protection. This brings us to a crucial third point: AI.

As Peggy Hicks, Director, Thematic Engagement, Special Procedures and Right to Development Division, UN Human Rights Office (OHCHR) demonstrated during a session on AI – moderated by Lauren Perry, Responsible Technology Policy Specialist, Human Technology Institute – when we talk about safe and responsible AI, “ethics” often gets the spotlight. Ethical AI sounds good on paper, but reader beware – ethics are usually voluntary. Children need stronger guarantees that ensure safety isn’t a second thought but a prevailing guardrail based in international consensus.

If we want AI that is safe, fair and rights-based, we need more than just good intentions. We need to build on the proven and enforceable standards we already have. Human rights frameworks offer a clear and binding path forward, providing the backbone for a digital future that truly protects everyone.

This is because human rights frameworks:

- Are grounded in binding international law, not just principles.

- Have decades of global consensus and robust guidance behind them to turn principle to practice,

- Offer practical direction for both governments and businesses.

Therefore, by mapping AI guidance through a human rights lens, we can:

- Build on what’s already been decided.

- Create a clear flow from principle to practice.

Lay foundations for delivery that respect people’s cultures and needs. ust about avoiding risks; it’s about teaching kids to navigate the digital world with confidence and responsibility.

What’s next

Pacific Cyber Week underscored a simple truth: connection without protection is a bad deal for children, and their communities. We can take some big steps towards levelling that equation by ring-fencing their data, teaching skills that stick, and holding AI to the same human rights standards we expect offline.

Want to do more? If you’re building digital literacy in your school or community, explore ChildFund’s Swipe Safe app and curriculum. It’s a practical starting point while we work towards systemic changes for children.