When you ask Jane why she decided to study electrical work, her response is simple: “Because I liked it.”

She grins. Then she adds: “I wanted to help people. And I wanted to show other girls that there is no course they can’t take.”

This is how we’re sparking new employment opportunities for youth in Kenya.

How many young people are unemployed in Kenya?

Where Jane lives in Kiambu County, Kenya, a rural community known for its sprawling coffee farms, it’s unusual to see a young woman entering such a traditionally male-dominated industry. In fact, youth unemployment in Kenya is high regardless of gender.

According to the country’s 2018 Basic Labour Force Report, more than 11 percent of youth aged 15-34 in the country are unemployed, putting them at risk of poverty and homelessness.

The dangers are even greater for unemployed or low-income girls in this age group, who face higher rates of teen pregnancy and gender-based violence than their peers.

But Jane has the confidence of a girl who knows she’s going places, thanks in part to ChildFund’s job training programs, which focus on the specific needs of young adults.

How are we reducing unemployment in Kenya?

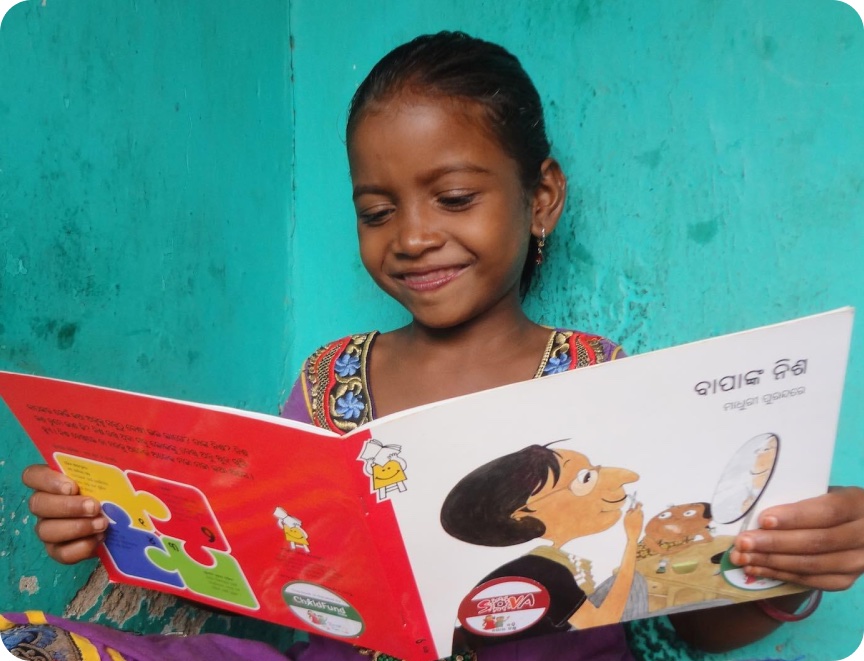

Our Youth Vocational Skills project in Kiambu County connects at-risk youth to job training programs that will give them a practical means of earning an income for life.

We train youth as electricians, carpenters, hairdressers, tailors, auto mechanics and more, providing full or partial scholarships to students who need them most.

When the students graduate from their training, ChildFund also supports them with startup tools so they can be prepared to find work or launch their own businesses and begin making money right away, helping to reduce youth unemployment in Kenya.

ChildFund scholarship to study hairdressing, as well as startup capital to open a salon.

“If I had not received this training, I would have probably been at home farming. But farming, for now, isn’t a good source of income,” says Jane. “In this area, even some who have completed university have no job. But if you take vocational training, it is hard to fail in getting one.”

Jane is currently in the final stage of her studies, after which she plans to seek an electrical apprenticeship and use her skills to light up homes, schools and everything in between for disadvantaged people in her community.

Become a vehicle of change and help reduce unemployment in Kenya

You can become a vehicle of change and help us reduce unemployment in Kenya. There’s a couple of ways you can help change lives:

- Make a regular monthly donation: Donating monthly through ChildFund is an effective strategy that provides a child and their family with access to funding, training and programs that will help improve the child’s future opportunities.

- Donate where it is most needed: When you donate to us, we’ll allocate your donation to make the most impact across our projects.

It only takes one person to change the life of a child.